I love history

When I was 20, I didn’t know that I loved history. When I was 30, I had minored in history. Now, past 40, I’m developing opinions about history. Sometimes I wonder whether I should gather all these history-related ideas together into one blog post, but I think not. I’m thinking as I go… isn’t it better to be invited on a hike and admire the view as you go along than to have a friend present you with with an album of their souvenirs? Blogging is like inviting you along…

I like it when I find myself nodding along with what a podcast guest is saying. This week it was to Paul Kingsnorth on the podcast Honestly with Bari Weiss (here). To establish your values, he argues, you need “people, place, prayer, and the past”. About the past, you can ask yourself: “What’s your sense of the past, your sense of history? How can you live that? How can you honour your ancestors, pass things on to your children?” I think about this often and enjoy the challenge it presents.

What kind of challenge does thinking about history present? The first one is relevance. When I say relevance, it makes me think of people who say that history is boring and I so I think about the things that make history boring (like cliché) and the things that make it interesting (story) and I glow incandescent when I hear academics broach these themes exactly. I thoroughly enjoyed stumbling upon this interview between Dan Wang and Stephen Kotkin on Youtube (here).

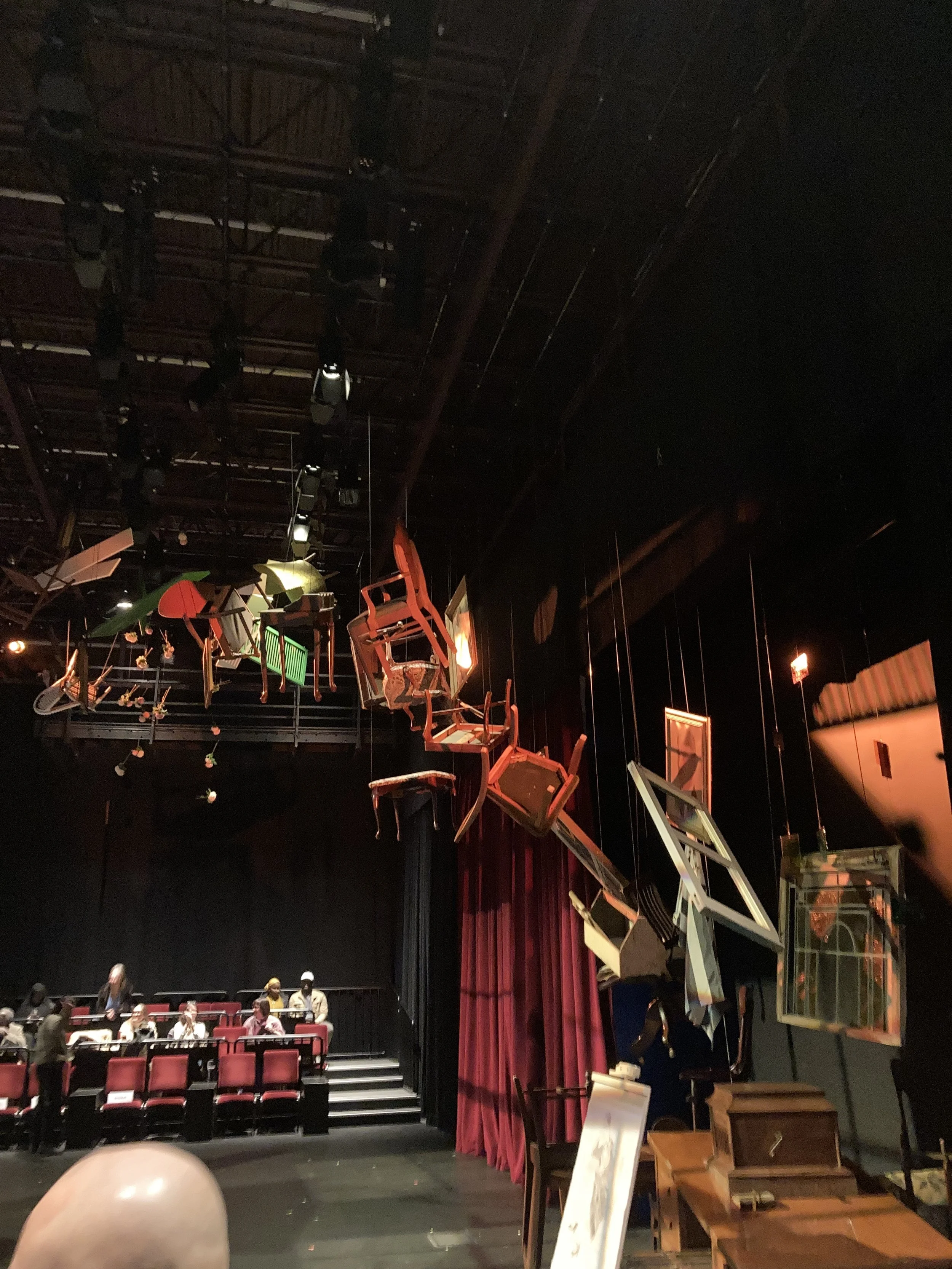

Cercle Molière

Last weekend we attended a play at the French theatre, the subject of which was Pauline Boutal’s life. (I read her biography earlier this year and I’m so happy I did - I doubly enjoyed the play!)

Going to plays in French was my husband’s idea, and this one was the first of this season… I don’t know why or how I managed to have such low expectations of theatre, but my gosh, I found myself discreetly crying actual tears. The actors disappear after we applaud at the end, and in the emotion of the moment, applause felt too little, too small an act… they deserved hugs! A round of drinks on the house! Cheers to their talent, more cheers for health and a long life!

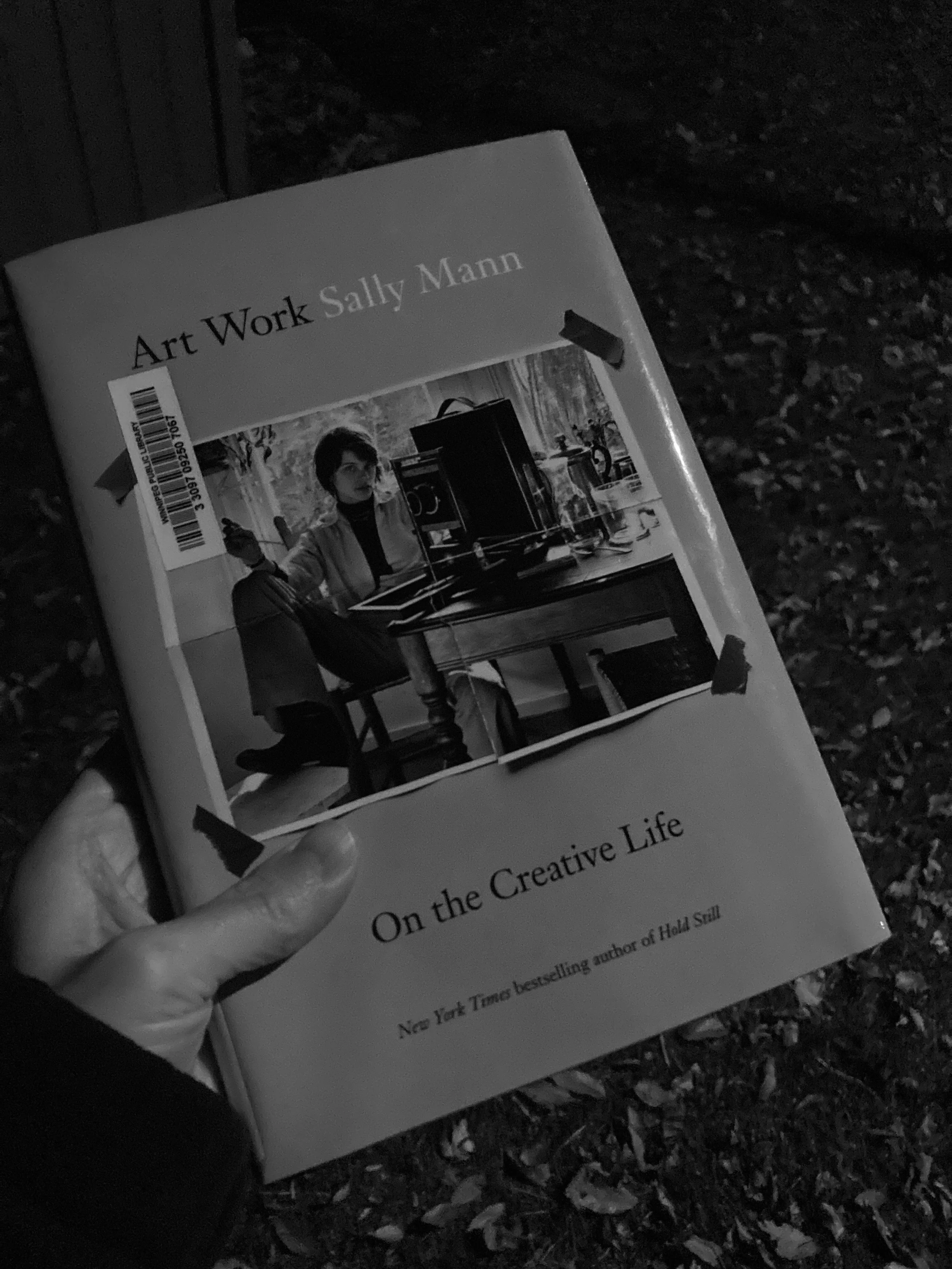

Reading

I finished Art Work by Sally Mann. It contains lots of quotes. Lots of lovely-long sentences. Advice given as if she suspected her reader might roll their eyes, but also as if she knew she had the authority to give it (that is, sometimes the tone felt self-deprecating, sometimes haughtily impatient). I liked her stories… the terrible renter fiasco, the incredible trip to Qatar. Dear Mrs. Mann: more stories please?

The thing is, I really enjoyed reading Hold Still (mentioned here in 2018). The image of a person’s death being like a library burned to the ground has often come to mind, and it’s from the end of that book. She writes:

I have long been afflicted with the metaphysical question of death: What does remain? What becomes of us, of our being?

Remember that song by Laurie Anderson in which she says something about how when her father died it was as though a library burned to the ground? Where does the self actually go? All the accumulation of memory - the mist rising from the river and the birth of children and the flying tails of the Arabians in the field - and all the arcane formulas, the passwords, the police recipes, the Latin names of trees, the location of the safe deposit key, the complex skills to repair and build and grow and harvest - when someone dies, where does it all go?

Proust has his answer, and it’s the one I take most comfort in - it ultimately resides in the loving and in the making and in the leaving of every present day. It’s in my family, our farm, and in the pictures I’ve made and loved making. It’s in this book. “What thou loves well remains.” […]

Love! The world needs Love!

In the kitchen

This week, I made Zaynab Issa’s “Ultimate tuna melt” from her cookbook Third Culture Cooking and the kids told me not to lose the recipe. Very high praise!

For dessert: Apple Pudding Cake. Delicious!

Enjoying

Freakonomics podcast is doing another series and I’ve been delightedly pulled-in. All Stephen Dubner’s research into horses has reminded me of when I was young… I read Black Beauty and wanted a horse. I was a child in the middle of Saskatoon with no concept of what horse-ownership entailed. My dad discouraged the idea. He said horses could have a temperament. I figured he’d not read Black Beauty.

My mom also liked horses, but from a distance. Her brother had worked with horses. We watched National Velvet together… I knew about the Triple Crown and Secretariat and nothing about The Adams Family. In teenager-hood, I read Monty Roberts’ book The Man Who Listens to Horses (which, in my flawed memory, was titled “The Horse Whisperer” but Google refutes me). Mom and I were fans of people who could perform feats in animal behaviour. Then I grew up and horses left my mind. These podcasts are a nice (current!) revisit to that world!

Writing

Really liked this substack post by Gen Zero titled “Everyone is a strategist and No One is a Writer” (via) especially this concluding bit:

As we focus on how marketing is done, substantive questions of the world itself get sidelined.

Implicit in this focus on marketing is a focus on everyone but oneself.

I’ve noticed oak galls in the past and even mentioned them here but never gave them any further thought. But woah! Wasps are involved! What a lovely substack post! (Via)

Christmas approacheth

I admire a person who can make craft projects feel almost un-craft-like. I’m not sure how to explain it except that Naomi Vizcaino - with her references to the past and the originality of her ideas - makes her project ideas feel especially artistic. (TikTok)

Postcards

Here is my dog, not barking at another dog.

Here is milkweed with floss so soft I think of a grandmother’s hair.

Here is a view of the fallen tree across the river.

Here, through a tangle of trees, I spy some that seem almost decorated in the sunlight… red berries, leaves that shimmer…

And behold! Captured here is the first snow!

Happy Sunday!