Behind the beautiful forevers

I’d feel a little deflated every time I finished reading a chapter from this book, but never dissuaded from picking it back up the next day. The low feeling had the effect of an unexpected take-off at the end… a kind of moral that sparkled like a discovery dissimulated from view until the final chapter. I therefore appreciated this quote, taken from one of the book’s subjects: “For some time I tried to keep the ice inside me from melting. […] But now I’m just becoming dirty water, like everyone else. I tell Allah I love Him immensely, immensely. But I tell Him I cannot be better, because of how the world is.” (p 241).

In her author’s note, Katherine Boo writes:

In the age of globalization - an ad hoc, temp-job, fiercely competitive age - hope is not a fiction. Extreme poverty is being alleviated gradually, unevenly, nonetheless significantly. But as capital rushes around the planet and the idea of permanent work becomes anachronistic, the unpredictability of daily life has a way of grinding down individual promise. Ideally, the government eases some of the instability. Too often, weak government intensifies it and proves better at nourishing corruption than human capability.

The effect of corruption I find most under acknowledged is a contraction not of economic possibility but of our moral universe. In my reporting, I am continually struck by the ethical imaginations of young people, even those in circumstances so desperate that selfishness would be an asset. Children have little power to act on those imaginations, and by the time they grow up, they may have become the adults who keep walking as a bleeding waste-picker slowly dies on the roadside, who turn away when a burned woman writhes, whose first reaction when a vibrant teenager drinks rat poison is a shrug. How does that happen? How - to use Abdul’s formulation - do children intent on being ice become water? A cliché about India holds that the loss of life matters less here than in other countries, because of the Hindu faith in reincarnation, and because of the vast scale of the population. In my reporting, I found that young people felt the loss of life acutely. What appeared to be indifference to other people’s suffering had little to do with reincarnation, and less to do with being born brutish. I believe it had a good deal to do with conditions that had sabotaged their innate capacity for moral action.” (253-54)

The above set up a kind of intellectual precondition for reading every word of this whole long substack article by Edward Zitron who writes at one point : “Everything is dominance, acquisition, growth and possession over any lived experience, because their world is one where the journey doesn’t matter, because their journeys are riddled with privilege and the persecution of others in the pursuit of success.”

Recently, at the Munk Debates, Ezra Klein relayed a quote from Charles Mann. Klein narrates:

The writer Charles Mann tells a story. He’s at a wedding in the Pacific Northwest […], he’s at a table with all these 20 somethings who want to make the world better, who see the ways in which it currently falls short. And it’s not that they’re wrong, he writes, but he says, ‘the heroic systems required to bring all the elements of their diner to these tables by the sea were invisible to them. Despite their fine education, they knew little about the mechanisms of today’s food, water, energy, and public health systems. They wanted a better world, but they didn’t know how this one worked.’

Mann’s quote is eloquent, and I would argue that both are writing in parallel on the issue of morality… Zitron writes in the same article:

We train people — from a young age! — to generalize and distance oneself from actual tasks, to aspire to doing managerial work, because managers are well-paid and "know what's going on," even if they haven't actually known what was going on for years, if they ever did so. This phenomenon has led to the stigmatization of blue-collar work (and the subsequent evisceration of practical trade and technical education across most of the developed world) in favor of universities. Society respects an MBA more than a plumber, even though the latter benefits society more — though I concede that both roles involve, on some level, shit, with the plumber unblocking it and the MBA spewing it.

He, like Mann, like Boo, is pointing to similar symptoms of a societal ill.

Food

Last week I had friends over for lunch and made a sweet little windowsill bouquet for the occasion.

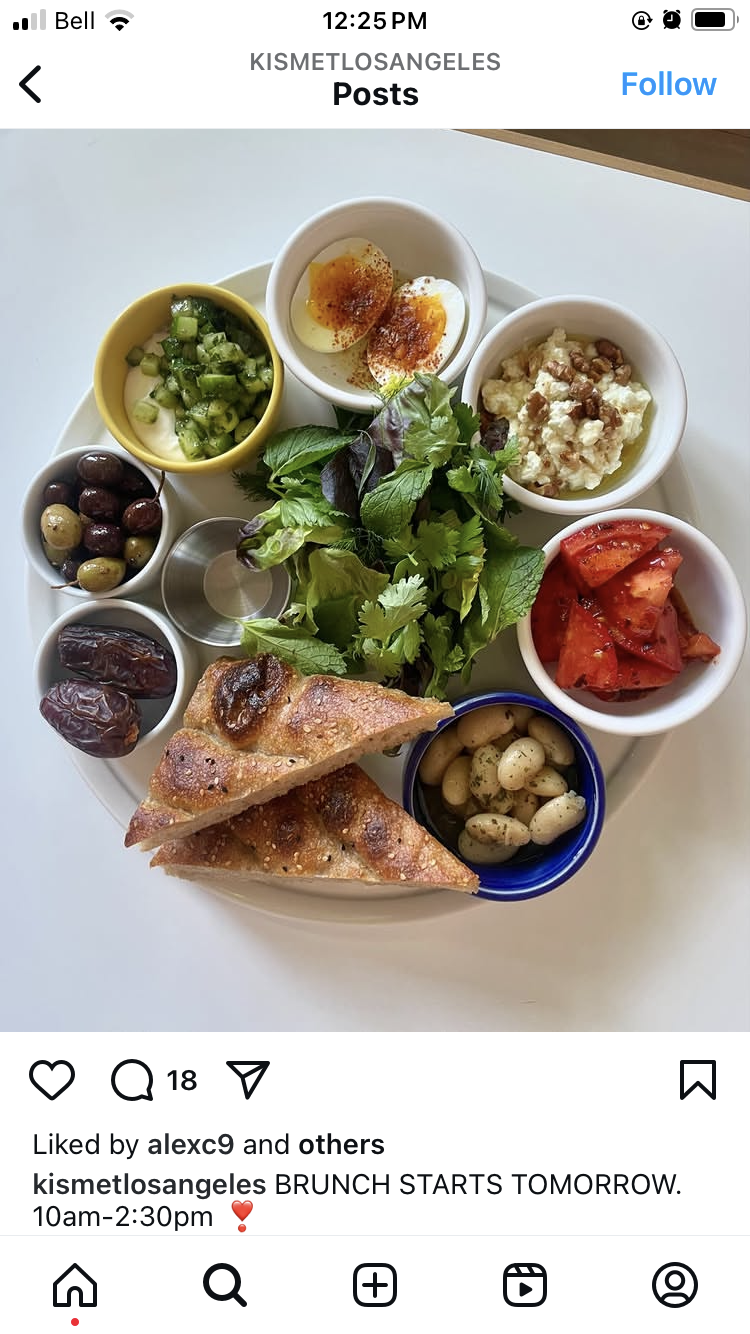

But even more fun was building a little menu inspired by KISMET cookbook recipes. The idea was to serve a bunch of things to nibble on, as they featured on Instagram

or written about here. I’m so pleased that in Winnipeg, you can find ingredients for Marinated Feta with Dates + Rose Water Onions and Kale Tahini with Pomegranate Molasses and Garlicky Bean Dip that has an alluringly salty olive topping made with oil-cured Moroccan olives by stopping by De Luca’s for fresh bay leaves, Blady Middle Eastern for good tahini, rose water, and oil-cured Moroccan olives and Vita Health for lacinato kale. Were it not for cookbooks that show readers how to use ingredients and treat their taste buds, I wouldn’t feel encouraged to visit these smaller stores.

Lazy dog

As summer hits, bringing warm weather and sunny days, Enzo leaves fur behind and chooses air-conditioned interiors.

Postcards

This week features a little collection of bugs… The first, my sister informed me, is a fly that looks like a bee. To the left, slightly out of focus are two stink bugs, lumbering about, like heavily-armoured plunderers!

I suspect this second one, inert and cozy, is a napping bee. I love the beautiful white anemones, and always check the centres of their pretty five-petalled flowers to see what they invite. This one had two visitors at once!

The third is a mayfly, a dramatic silhouette for a dramatically short life…

Wishing you nice week ahead!