Teaching myself to swim

Friday was the tenth time I put on a bathing suit, cap and goggles and slid myself into a city pool with the firm intention of getting over my fear of water. As an experiment, it has been going well. My goal is to be able to swim laps with Christian. Meantime, I stay in the shallow end, learning buoyancy, while he goes back and forth and tests ever higher diving boards. I think that an account is due, a little summary of the impressions I have of the experience so far, before I forget what learning to swim felt like.

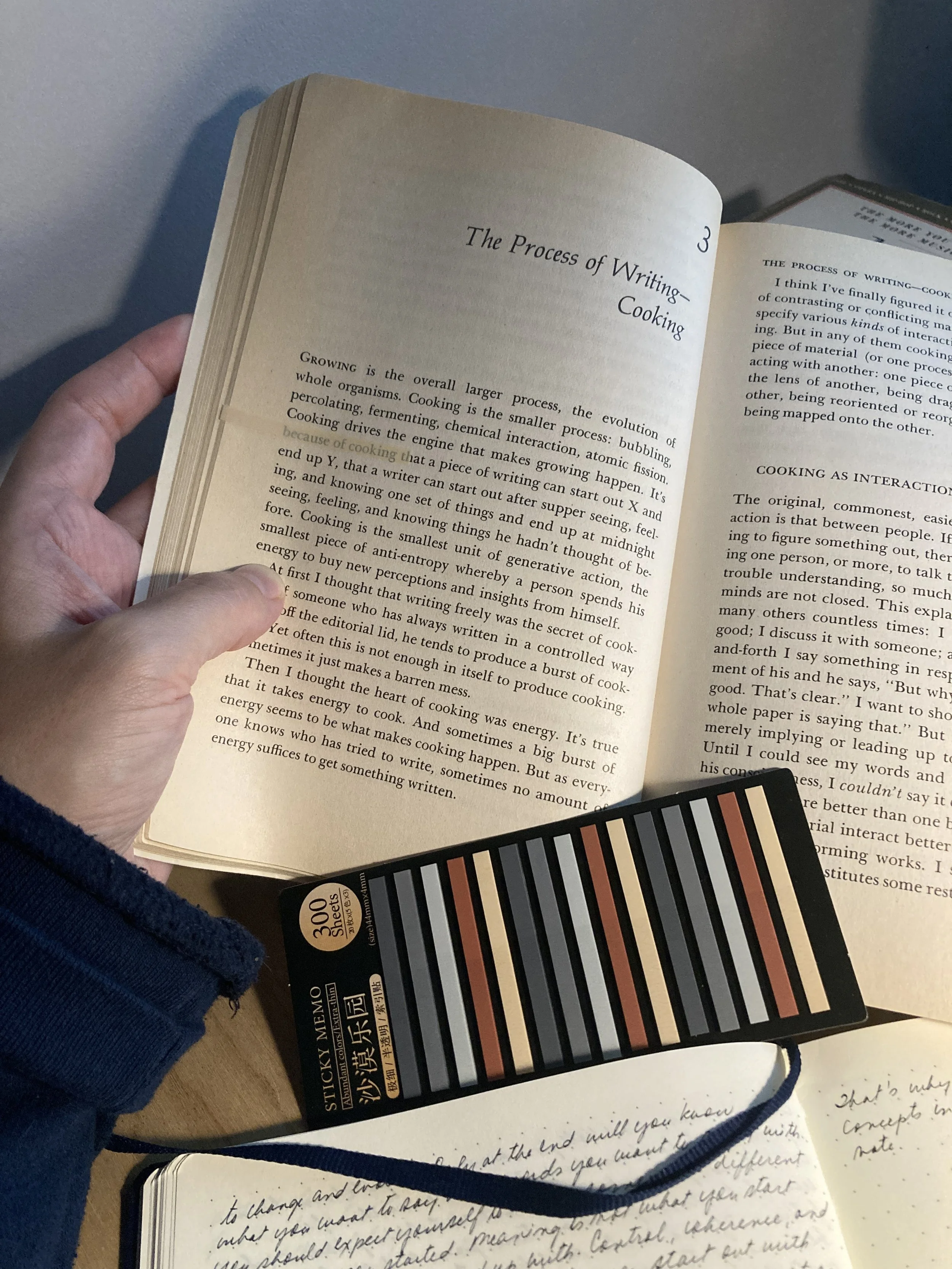

An unexpected feeling. I’ve learned that there’s a distinction between feeling “enthusiasm” for something and feeling “invigorated” by something. An idea can create enthusiasm, but it can be temporary. Its definition associates it to speech: “she enthused” or “she spoke enthusiastically”. By contrast “invigorate” feels more stable and less superficial. It is “to impart vigour to; to fill with life and energy; to strengthen, animate”. I’ve had ideas for projects in the past, talked about them, felt enthusiastic, and fed myself on other peoples’ reaction. But it quickly wears out. Having a practice, like writing or drawing, has taught me persistence beyond the idea-phase because I can see that incremental improvement happens over time, despite feelings of impatience.

One of the first instructor’s advice I followed was Kaitlin Frehling’s video. It begins by teaching buoyancy. I wasn’t able to follow her instructions until the third visit to a pool, but finally being able to gather myself into a ball while gently exhaling under water and feeling my back bob to the surface was a brand new sensation I was thrilled to repeat and repeat. My brain forgot to be okay with this feeling by the next visit, but picked it up again fairly quickly. Feeling this happen and observing the brain learn was very invigorating!

Learning technique. Swimming is so technical that breaking it down into steps is a little puzzle on its own. There is theory and application… but a big part of learning how to apply something is learning how to digest it in pieces that don’t lead to overwhelm. When I told my sister I was teaching myself to swim, she asked me why I didn’t just take lessons. The thing is, a big part of learning to swim is just getting over my own fear of the water… I understand technique quite well, and there’s a plethora of Youtube videos for every kind of technique.

Videos that don’t break down technique are instructive in their own way. Take “Learn to Swim as an Adult” which compresses into three episodes Harry getting over fear of water in the first, learning front crawl in the second, and going at it in the deep end in the third; all within a month. The instructor is encouraging, and Harry is a good sport, but there looms over this production a feeling of “Ugh, why won’t this just come together?” expressed in Harry’s comment “it is frustrating…”. The technique is there, but really, what Harry needs, and what the Youtube channel doesn’t specialize in showing, is a whole bunch of time dedicated to getting comfortable with being in the water. I suspect that actual footage of an adult learning to swim is boring. More fun for the viewer is the exciting montage you tend to find in movies. More useful for the adult learner are the techniques that can be applied visit to visit. The two objectives are at odds in the above example, but there are other instructors who target their audience well by giving them very small steps to try on their own.

Pausing here to acknowledge fear. I want to take a minute to appreciate various sources of encouragement… Articles like Alexandra Hansen’s “Learning to swim as an adult is terrifying, embarrassing and wonderful” for The Guardian or videos like Dan Swim Coach’s “How to Overcome Fear of Water” and Sikana’s “Overcome a fear of water” treat this feeling seriously. They also emphasize the key to overcoming it by exposure. Exposing myself to water again and again and again is a small doable step and I’m happy after every time I take it.

Breaking down technique into small and smaller steps. I’ve mentioned Kaitlin Frehling above, and have used the PDF “Beginner Swim Resource” illustrating routines you can do to learn to swim, as a guide. But I do have a slower pace… For example: week 5 workouts introduce a swimmer’s snorkel. I’d never tried a snorkel before, and I had to confront the sensation of water in my nose. I’d been avoiding this by gently breathing out of my nose underwater and not just holding my breath. The first attempt - my 7th visit to the pool - I had to get past the panicky feeling. Between weeks 7 and 8 I watched Youtube tutorials (this one and this one) on snorkel use. Pool visits then included time gradually getting used to breathing with a snorkel for 2, then 4 then 6 lengths, with flippers and then without. But I don’t begrudge the extra time I’m taking, because there’s no one to impress but myself.

Supporting local We visit our favourite city pool Friday evenings and it feels nice to be connected in this way to a service we now support. We’re starting to recognize regulars, becoming ones ourselves… And I found swimming gear I needed from a local business called Swimming Matters. All these things are motives for gratitude!

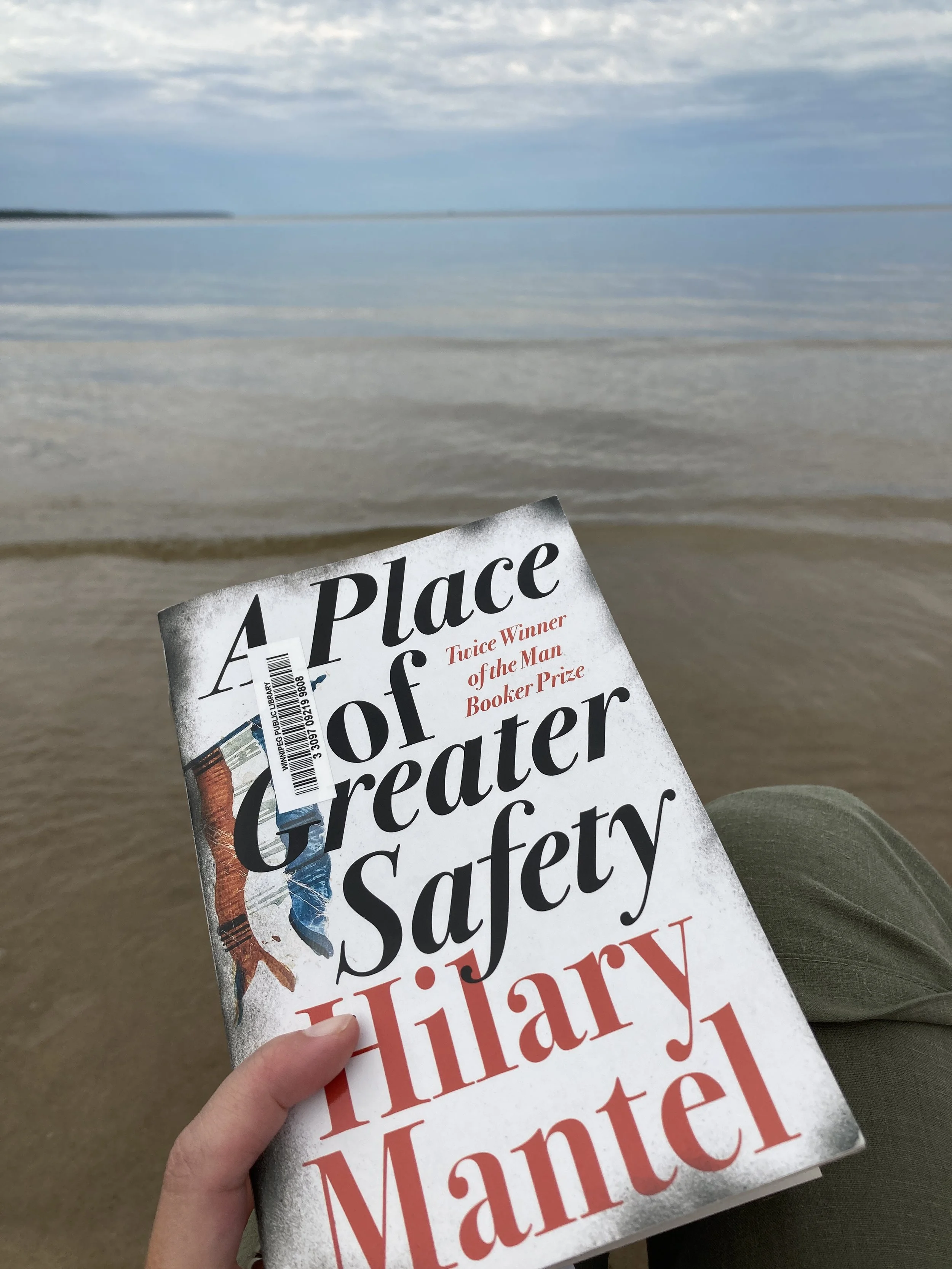

Reading

I think the book 1177 B.C. by Eric H. Cline was recommended by a podcast guest for its final chapter detailing the collapse of civilisations and the end of the Bronze Age, because of the “eerily prescient” (in Adam Gopnick’s words) conditions it highlights.

Personally, I liked the difference between then and now that the author highlights in this passage:

I should hasten to add that, although it’s clear that climate change and such factors as pandemics have caused instability in the past, there is at least one major difference between then and now - concurrent knowledge of events unfolding. The ancient Hittites probably had no idea what was happening to them. They didn’t know how to stop a drought. Maybe they prayed to the gods; perhaps they made some sacrifices. But in the end, they were essentially powerless to do anything about it.

In contrast, we are now much more technologically advanced. We also have the advantage of hindsight. History has a lot to teach us, but only we are willing to listen and learn. If we see the same sort of things taking place now that happened in the past, including drought and famine, earthquakes and tsunamis, then I ask again, might it not be a good idea to look at the ancient world and learn from what happened to them? Even if the various problems at the end of the Late Bronze Age were “black swan” events, as Magnus Nordenman has suggested, the mere fact that we have so many similar problems at the present time should be cause for concern.

Enjoying

This definition of taste in a substack by Henry Oliver, written two years ago, is so clear, I’ll likely go back and reread it again.

Baking aspiration

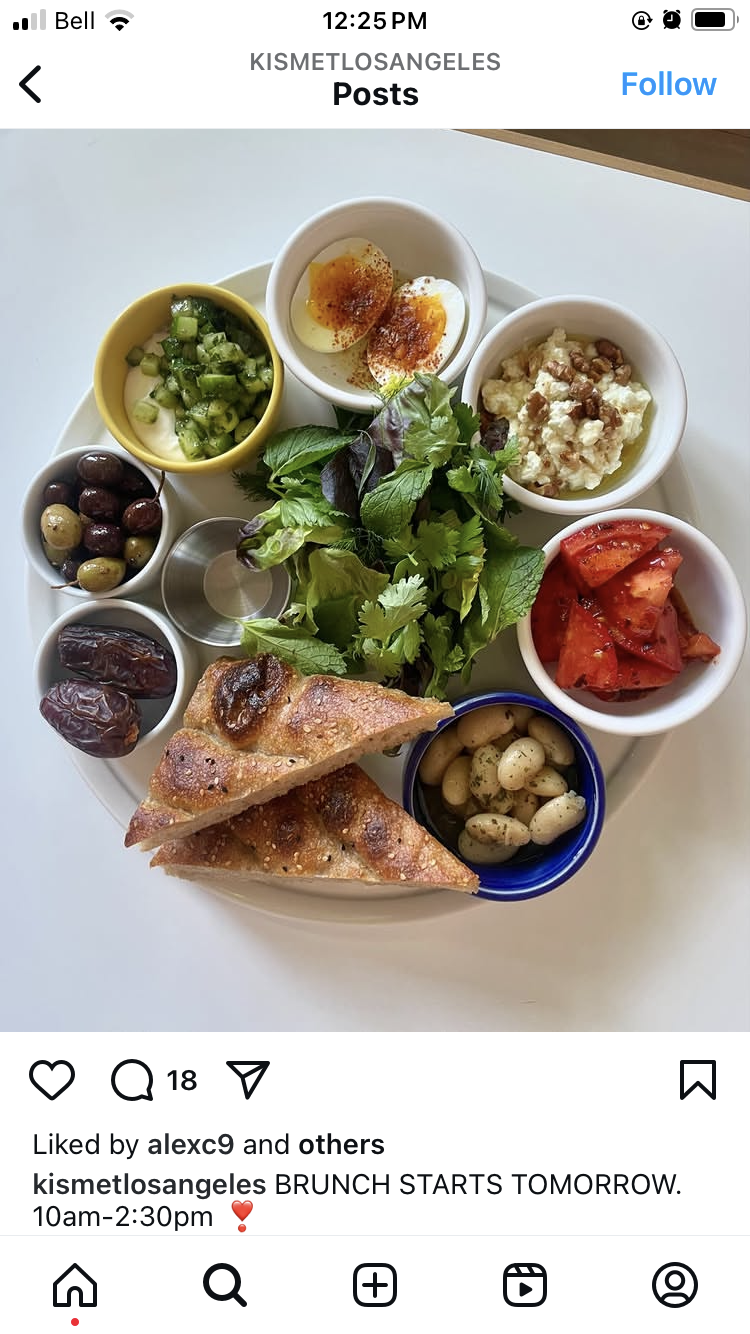

There’s nothing like a baking project to inspire confidence in pulling off your own roundup of cookies at this time of year, and I’ve been enjoying Justine Doiron’s cookie advent-calendar she made over four (!) days. (On Instagram here.)

Postcard

This week: snow on the river!

Happy Sunday!